Meteorites! What’s all the fuss about? They’re just boring old lumps of rock. Black or grey, rough or smooth, a rock is a rock!

Of course, everyone is entitled to their opinion, but meteorites are no ordinary rocks. They are the oldest objects you can handle. Some contain grains that predate our Solar System and organic compounds that were probably formed in interstellar space. There is a whole list of features that make meteorites simply extraordinary. We’ve been through it all before in previous posts.

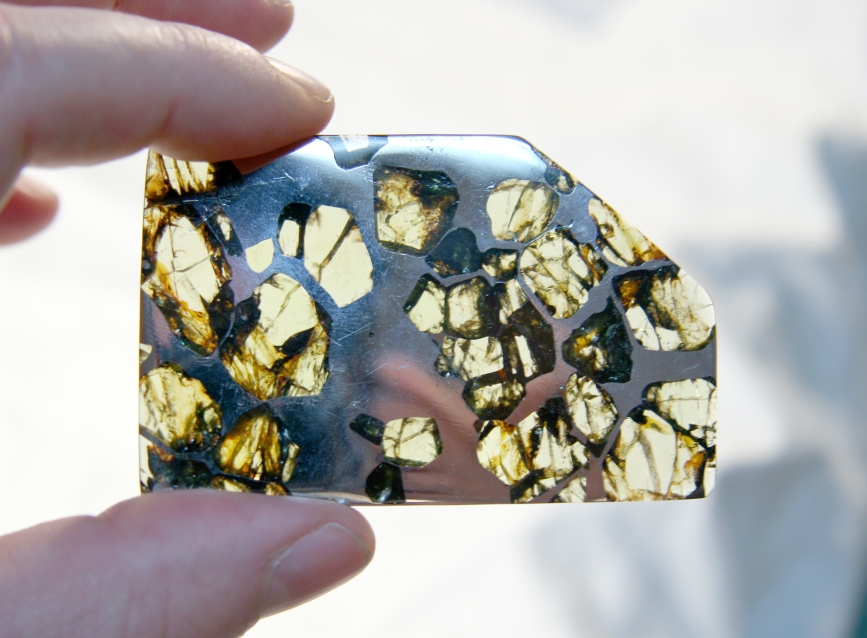

Well, not quite! There is one important feature I forgot to mention in those earlier articles; meteorites can also be extremely beautiful objects. The most obvious examples are pallasites, which when cut to the thickness of a wafer allow light to pass through the large olivine crystals that are embedded in Fe, Ni metal. A well-prepared pallasite slice is, without doubt, a thing of exquisite beauty.

Esquel pallasite showing large olivine crystals enclosed by Fe, Ni metal (image Doug Bowman/Wikipedia)

Esquel pallasite showing large olivine crystals enclosed by Fe, Ni metal (image Doug Bowman/Wikipedia)

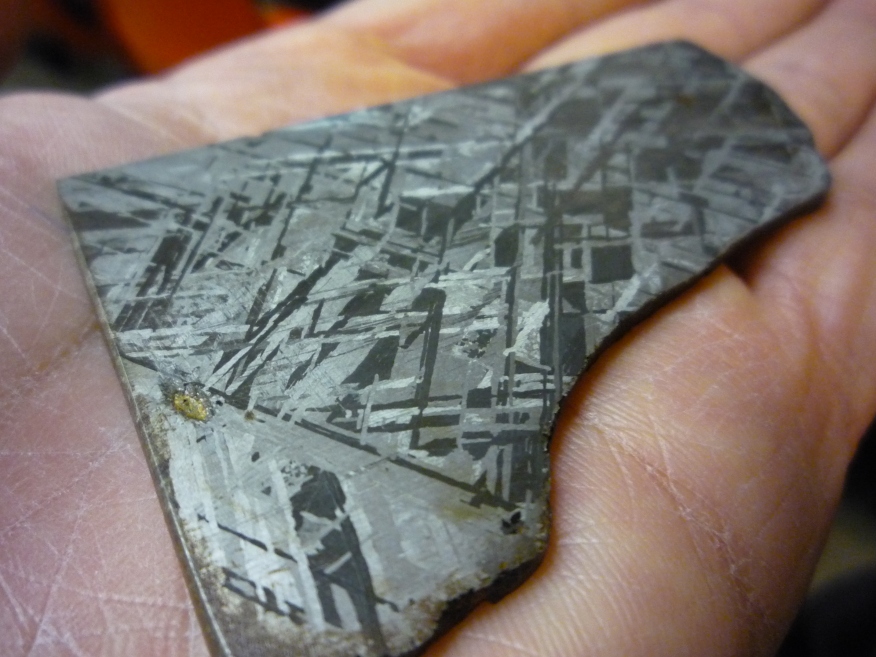

And then there are the irons. Cut, polished and etched to bring out their intricate Widmansttaten patterns, irons are objects of fascination and wonder. And their beauty is enhanced when you come to understand that these are fragments from the heart of an extinct asteroid, battered to bits in an ancient cosmic cataclysm.

Cut and polished slice of an iron meteorite showing Widmanstatten pattern (image: Wikipedia)

But what about stones, by far and away the largest meteorite type, can they also be beautiful? Well, until recently, I would have had to concede that, while they are the scientific equivalent of treasure trove, most stones are not particularly beautiful objects.

So why have I changed my mind?

That’s simple. It’s all down to a new set of meteorite images from the Virtual Microscope team, painstakingly collected by Dr Andy Tindle, in partnership with Dr Caroline Smith and Professor Sara Russell of the Natural History Museum. These are of British and Irish meteorites, mainly historic falls, held in various museum collections. For many of these specimens, both a fully rotatable hand-specimen view and zoomable thin-section images are available. The level of detail that can be obtained as you zoom in to study these samples if often breathtaking. This new Virtual Microscope collection is not only fun, it is also a very useful research tool. Here are a few examples to show you what I mean:

Many of the hand-specimens retain a significant portion of their fusion crust, which is the thin black, glassy layer that formed during heating, as the meteorite decelerated in the Earth’s atmosphere. In a number of examples, most notably Ashdon, distinct flow lines are visible, formed as molten material was swept off the back of the meteorite during its flight through the atmosphere.

Fusion crust is a thin, dark, glassy layer on the outside of a meteorite that forms due to melting as a result of frictional heating during deceleration in the Earth’s atmosphere. (image: NASA)

The fragment of the Barwell meteorite shown in the collection is particularly interesting as it contains a large rounded igneous inclusion (1.5 x 1.2cm). This object was the subject of an important study led by the late Robert Hutchison, which found that the Barwell “pebble” had formed by melting on an asteroid that was older and compositionally distinct from the one that the Barwell meteorite came from. So this single sample is a witness to the complex and often violent history that took place during the formation of our Solar System about 4,567 million years ago. In the paper by Hutchison and co-workers, only a simple sketch drawing of the Barwell fragment was provided. Now, thanks to the Virtual Microscope, this specimen is available for all to examine in ultra high-resolution!

Barwell, Leicestershire, where on December 24th 1965 a shower of stones fell, with a total recovered mass of at least 44 kg. (image: Robert Smith/Leicestershirevillages.com)

Perhaps the most important meteorite in the collection is Pontllyfni, which fell on the mainland coast of Wales, not far from Anglesey, in 1931. Pontllyfni is a winonaite, an important group of stony meteorites that formed by melting on an asteroid early in solar system history. Out of 27 recognised winonaite samples listed on the Meteoritical Bulletin Database, Pontllyfni is the only fall, making it a particularly important specimen. It is also controversial. Winonaites are transitional between chondrites, which contain chondrules, and achondrites, which don’t. So does Pontllyfini contain chondrules? Some have claimed that it contains relict structures that were originally chondrules. You can make up your own mind by looking at the polished section available on the Virtual Microscope.

The large circular features in this image are chondrules. They are generally believed to have been formed as molten droplets is space and were subsequently incorporated into an asteroid. Have a look at the thin-section of Pontllyfini on the Virtual Mircroscope and see if you can spot any of these objects. (Image: Richard Greenwood, plane polarized light, field of view ~ 1mm)

So, meteorites are fascinating and important objects and, as I think I have shown, beautiful too, even the stones. But don’t take my word for it, visit the Virtual Microscope and see for yourself. Have fun!

On the 4th August 1835 a single stone weighing about 700 g plus a shower of smaller stones fell about half a mile away from the tiny village (one pub, no houses!) of Aldsworth, Gloucestershire. Take a look at the specimen on the Virtual Microscope. (image: Richard Greenwood)

Thanks for the links Richard

Most of the new British and Irish Meteorites collection is in the Natural History Museum who were partners in the project. I remember Andy spent several days down there photographing the specimens because they could’t leave the museum so its just about the only way to get a really close look at a meteorite, fusion crust and all.

I know there are more interesting samples scientifically but I still think the Iron meteorite Rowton ( http://www.virtualmicroscope.org/content/rowton ) makes the most amazing 3D object. It really just looks… alien.

Simon

LikeLike

Hi Simon

I agree, Rowton is a fantastic specimen and also scientifically important. The Meteoritical Bulletin Database lists 299 IIIAB iron specimens, of which only 11 are falls, including Rowton. I highlighted Pontllyfini because it really is unique, the only winonaite fall worldwide. But in a beauty contest Rowton would win, hands down!

Cheers

Richard

LikeLike

thank you realy a good article

https://m.youtube.com/?gl=FR&hl=fr#/watch?v=NaepmayaLdc

http://www.allmeteorites.com/?m=1

LikeLike

Thank you for your kind words

LikeLike

Reblogged this on 娯楽 and commented:

面白い

LikeLike

Hi there, I found your blog very interesting, specially this post, I mean I’m totally agree about that meteorites are amazing, just take a look to te ”Lovejoy” comet, it has alcohol and sugar and many other organic molecules flying in the universe… I think they are able to start life across many planets…

My name is Saúl and I write in my blog (Nightsky Sonora) about space stuff, I’m from Sonora (mexico) I just loved your blog. 🙂

Best regards!!!

LikeLike

Hi Saul

Many thanks for your kind words. I agree that meteorites are amazing and fascinating objects. As you point out, comets certainly contain a lot of complex organic molecules and also heaps of water. So yes, it is widely believed that early in solar system history comets may have brought the building blocks of life to our home planet. At the time Earth was probably a pretty dry and inhospitable place. So it is not impossible that we are all just pieces of a comet. A slightly crazy idea, but there you go!

LikeLiked by 1 person